On a crowded L train to Williamsburg one recent evening, I clasped my hand around the subway pole and scanned the multitude of hipster men surrounding me. As I studied the slim trousers ending just above sockless ankles, the plaid shirts encasing concave torsos, and the array of earnest tote bags, I spotted several men with full beards. Apparently these unfortunate hipsters were not aware that the style was on its way out (so 2013!), or maybe they were trying to get maximum benefit from their facial hair transplants. Certainly they were not East Asian, for whoever has met an East Asian man with the ability to grow a thick beard?

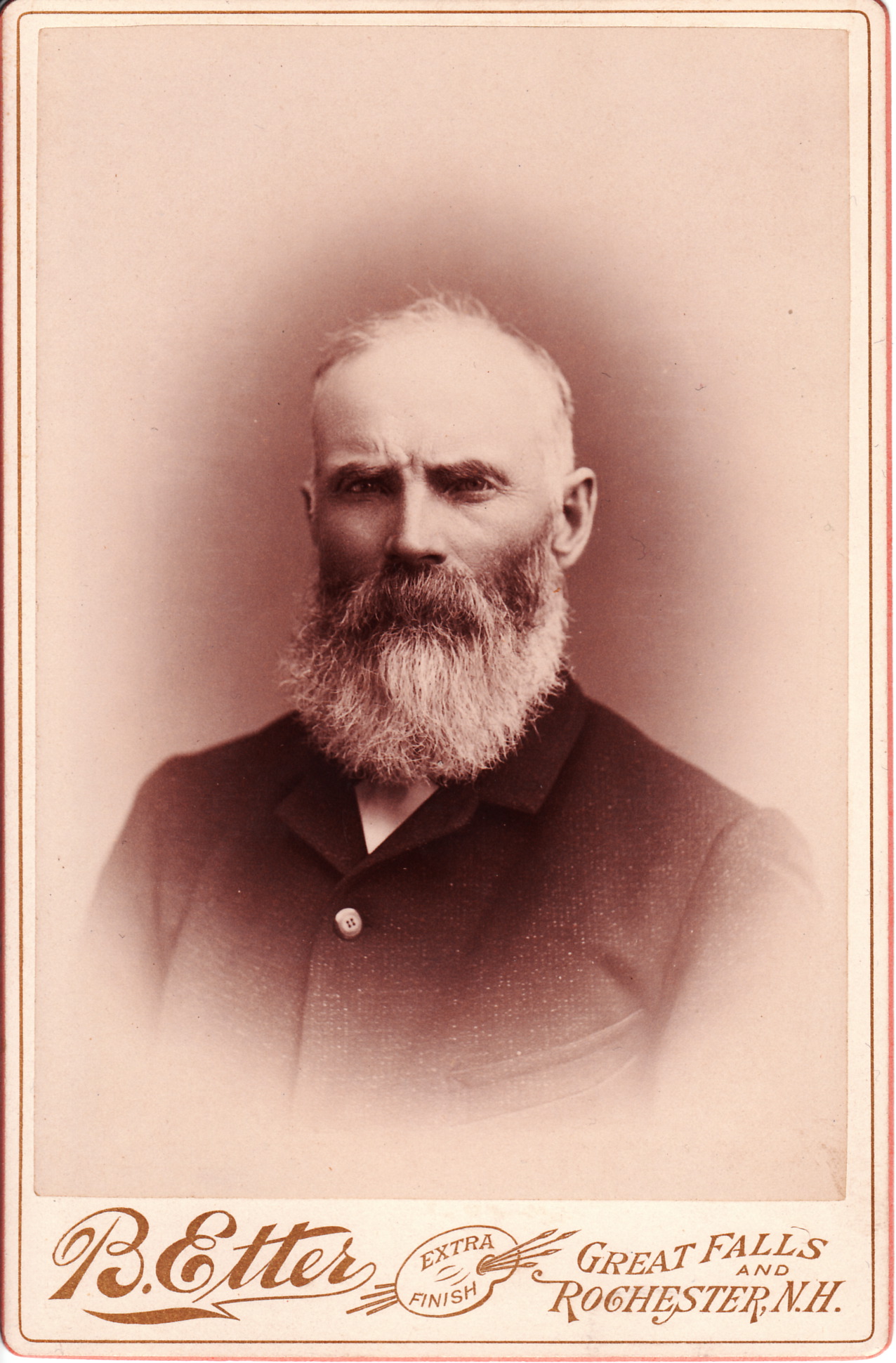

The embrace of facial hair by the hipster crowd has a historical precedent in the Victorian era, when full beards served as a symbol of masculinity and a stylistic corollary to the elaborate outfits and ornate home furnishings favored by fashionable contemporaries. Women clad themselves in long dresses with full skirts, bustles, and bodices, their hats topped with flowers, feathers, and, occasionally, entire stuffed birds. Men’s sartorial fashion was somewhat less extravagant, featuring neckties and waistcoats in rich fabrics like silk and brocade. At home, overstuffed sofas and armchairs, heavy drapes, and wall-to-wall carpets filled Victorian parlors. The preference for opulence even extended into bathrooms, which often contained luxuriant carpets and drapes, as well as ornamental wood cabinetry.

But in all of those folds of fabric and lush decorations lurked a hidden danger: germs. At the turn of the twentieth century, the leading causes of death were infectious and communicable diseases, especially tuberculosis, pneumonia, influenza, and diarrheal illnesses. Tuberculosis was particularly feared for the slow, painful death it induced in its victims; it consumed the body from the inside out, provoking a graveyard cough or “death rattle” in its final stages, when the patient’s gaunt appearance indicated that the end was near. In 1900, the disease killed one out of every ten Americans overall, and one in four young adults. Physicians had been able to diagnose tuberculosis accurately since 1882, when German bacteriologist Robert Koch identified the microorganism responsible for causing it. But this knowledge did nothing to improve a patient’s prognosis, for no cure existed. It wouldn’t be until after World War II, when antibiotics came into general use, that sufferers would finally have an effective remedy.

Koch’s discovery prefaced a new science of bacteriology. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the lessons of the laboratory began to reach into American homes and public spaces, changing individual behaviors and cultural preferences. Spitting was a particular target of public health authorities. Tuberculosis-laden sputum could travel from the street into the home on women’s trailing skirts; once inside, it dried into deadly dust that imperiled vulnerable infants and children. In cities across the nation, concerned citizens urged women to shorten their hemlines to avoid dragging germs around on their clothing. “Don’t ever spit on any floor, be hopeful and cheerful, keep the window open,” read one pamphlet. The common communion cup, once a familiar sight in Protestant churches, disappeared as it became implicated in the spread of disease. Hoteliers instituted a practice of wrapping woolen blankets in extra-long sheets that were folded over on top; when a hotel guest departed, the sheet was laundered to remove any tubercular germs exhaled during slumber. Homeowners ripped out the overstuffed upholstery and heavy fabrics of their Victorian-era interiors, replacing them with metal and glass. In bathrooms, white porcelain tiles and the white china toilet supplanted carpeted walls and floors. Preferences shifted to materials that could be cleaned of dust and disinfected, slick surfaces where germs would be unable to gain a foothold.

The stripped-down, modern aesthetic extended to personal style, as well. Women’s hemlines grew shorter, their silhouettes more streamlined. Men began to shed their full beards and moustaches in favor of a clean-shaven look. In 1903, an editorial in Harper’s Weekly commented on the “passing of the beard,” noting that “the theory of science is that the beard is infected with the germs of tuberculosis.” Writing in the same magazine four years later, an observer remarked upon the “revolt against the whisker” that “has run like wild-fire over the land.” By the 1920s, the elaborate fashions of the Victorian era were nowhere in evidence. Picture, for instance, a flapper-era female wearing a cropped hairstyle and a calf-length shift. Or the neatly trimmed moustaches of Teddy Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, the last two presidents to sport facial hair in their official portraits.

A century ago, men with full beards would have felt cultural pressure to shave to protect themselves and their families from the dangerous germs concealed within. It’s a sign of how much our understanding of bacteriology has changed that today’s hipsters harbor no such worries; indeed, few are probably even aware of the historical precedent of disease-laden facial hair. I was never a fan of the look to begin with, and now I can’t help thinking back to earlier fears of contagion whenever I see these beards. But short of a tuberculosis epidemic, which of course I don’t wish for, I’ll have to hope for some other imperative that will bring about a contemporary “revolt against the whisker.”

Sources:

Nancy Tomes, The Gospel of Germs. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.