As the New York Times reported last week, a recent study in the BMJ found that acetaminophen is no more effective than a placebo at treating spinal pain and osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. For those who rely on acetaminophen for pain relief, this may not come as much of a surprise. Until recently, I was one of them. Because my mother suspected I had a childhood allergy to aspirin, I didn’t take it or any other NSAIDs until several years ago, when I strained my back and decided to test her theory by dosing myself with ibuprofen. To my great relief, I didn’t die. And I was surprised to discover that unlike acetaminophen, which generally dulled but didn’t eliminate my pain, ibuprofen actually alleviated my discomfort, albeit temporarily. Perhaps my mother was wrong about my allergy, or maybe I outgrew it. Either way, my newfound ability to take NSAIDs without fear of an allergic reaction allows me to reap the benefits of a medication that can offer genuine respite from pain, rather than merely rounding out its sharp edges.

But back to the study. Just because researchers determined that acetaminophen is no more effective than a placebo in addressing certain types of pain doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s ineffective. A better-designed investigation might have added another analgesic to the mix, comparing the pain-relief capabilities of acetaminophen and a placebo not just to each other, but to one or more additional medications: say, ibuprofen, or aspirin, or naproxen. That would have enabled them to rank pain relievers on a scale of efficacy and isolate whether their results in the first study were due to the placebo effect (i.e. both acetaminophen and a placebo were effective), or to the shortcomings of acetaminophen (i.e. both acetaminophen and a placebo were useless).

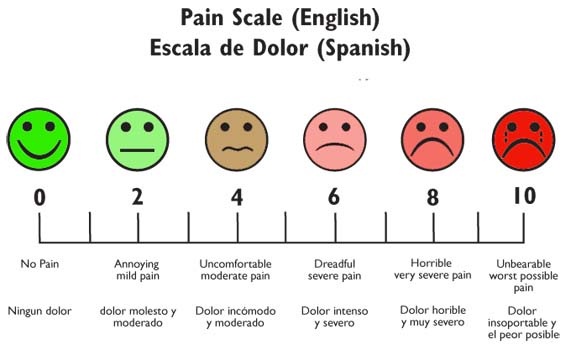

In any case, what I find noteworthy is not the possibility that acetaminophen might not work, but that a placebo could be effective. One of the foremost issues with the treatment and management of pain—and a major dilemma for physicians—is the lack of an objective scale for measuring it. Pain is the most common reason for visits to the emergency room, where patients are asked to rate their pain on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 indicating the absence of pain and 10 designating unbearable agony. Pain is always subjective, and it exists only to the extent that a patient perceives it in mind and body. This makes it both challenging and complicated to address, as the experience of pain is always personal, always cultural, and always political.

The issue of pain—and who is qualified to judge its presence and degree—unmasks the question of whose pain is believable, and therefore whose pain matters. As historian Keith Wailoo has written, approaches toward pain management disclose biases of race, gender and class: people of color are treated for pain less aggressively than whites, while women are more likely than men both to complain of pain and to have their assertions downplayed by physicians. Pharmacies in predominantly nonwhite neighborhoods are less likely to stock opioid painkillers, while doctors hesitate to prescribe pain medication for chronic diseases and remain on the lookout for patients arriving at their offices displaying “drug-seeking behavior.”

Whether the pain of women and people of color is undertreated because these groups are experiencing it differently or because doctors are inclined to interpret their perceptions in another way, it underscores the extent to which both the occurrence of pain and its treatment always occur in a social context. (In one rather unsubtle example, a researcher at the University of Texas found that Asians report lower pain levels due to their stoicism and desire to be seen as good patients.) Pain, as scholar David B. Morris has written, is never merely a biochemical process but emerges “only at the intersection of bodies, minds, and cultures.” Since pain is always subjective, then all physicians can do is to treat the patient’s perception of it. And if the mind plays such an essential role in how we perceive pain, then it can be enlisted in alleviating our suffering, whether by opioid, NSAID, acetaminophen, or placebo. If we think something can work, then we open up the possibility for its success.

Conversely, I suppose there’s a chance that the BMJ study could produce a reverse-placebo effect, in which this new evidence that acetaminophen does not relieve pain will render it ineffective if you choose to take it. If that happens, then you have my sympathy and I urge you to blame the scientists.

Sources:

David B. Morris, The Culture of Pain. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1991.

Keith Wailoo, Pain: A Political History. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014.