Recently I watched the first episode of The Knick, a new series on Cinemax that revolves around the goings-on at a fictitious hospital in turn-of-the-century New York. It stars Clive Owen as Dr. John Thackery, a brilliant and arrogant surgeon who treats his coworkers contemptuously but earns their grudging respect because he’s so darn good at his job. I’ve read that the show draws on the collections and expertise of Stanley Burns, who runs the Burns Archive of historical photographs. As a medical historian, I suppose it’s an occupational inevitability that I would view The Knick with an eye toward accuracy. Mercifully, I found the show’s depiction of the state of medicine and public health at the time to be largely appropriate: the overcrowded tenements, the immigrant mother with incurable tuberculosis, the post-surgical infections that physicians were powerless to treat in an age before antibiotics. I was a bit surprised by one scene in which Thackery and his colleagues operate in an open surgical theater, their sleeves rolled up and street clothes covered by sterile aprons as they dig their ungloved hands into a patient; while not strictly anachronistic, these practices were certainly on their way out in 1900. But overall, I was gratified to see that the show’s producers seem to be taking the medical history side of things seriously, even if they inject a hefty dose—or overdose—of drama.

A temperamental genius, Thackery thrives on difficult situations that call for quick thinking and improvisation. He pioneers innovative techniques, often in the midst of demanding surgeries, and invents a new type of clamp when he can’t find one to suit his needs. He is also a drug addict who patronizes opium dens and injects himself with liquid cocaine on his way to work. The character appears to be based on William Stewart Halsted, an American surgeon known for all of these qualities, right down to the drug addiction. Born in 1852 to a Puritan family from Long Island, he attended Andover and Yale, where he was an indifferent student, and the College of Physicians and Surgeons, where he excelled. After additional training in Europe, he returned to the US to begin his surgical career, first in New York City, then at Johns Hopkins Medical School. In addition to performing one of the first blood transfusions and being among the first to insist on an aseptic surgical environment, he was famously a cocaine addict, having earlier begun experimenting with the drug as an anesthetic. His colleagues covered for his erratic behavior, turning the other cheek when he arrived late for operations or missed work for days or weeks at a time. Twice he was shipped off to the nineteenth-century version of rehab, where doctors countered his cocaine addiction by dosing him with heroin. Although Halsted remained a cocaine addict all his life, he managed it well enough that by the time he died in 1922 he was considered one of the country’s preeminent surgeons and the founder of modern surgery.

Halsted pioneered another modern innovation, as well: the overtreatment of breast cancer. In the late nineteenth century, women often waited until the disease had reached an advanced stage before seeking medical treatment. As historian Robert A. Aronowitz writes, clinicians “generally estimated the size of women’s breast tumors on their initial visit as being the size of one or another bird egg.” When cancer was this far along, the prognosis was poor: more than 60 percent of patients experienced a local recurrence after surgery, according to figures compiled by Halsted.

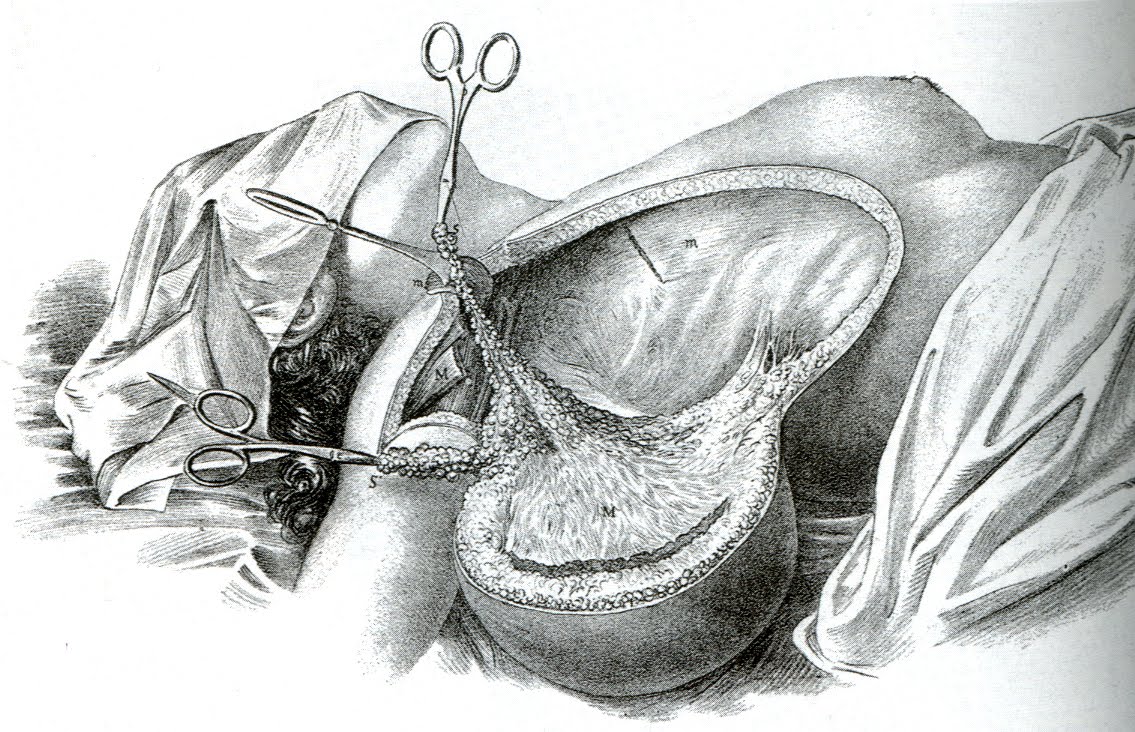

In the 1880s, Halsted began working on a way to address these recurrences. Like his contemporaries, he assumed that cancer started as a local disease and spread outward in a logical, orderly fashion, invading the closest lymph nodes first before dispersing to outlying tissues. Recurrences were the result of a surgeon acting too conservatively by not removing enough tissue and leaving cancerous cells behind. The procedure he developed, which would become known as the Halsted radical mastectomy, removed the entire breast, underarm lymph nodes, and both chest muscles en bloc, or in one piece, without cutting into the tumor at all. Halsted claimed astonishing success with his operation, reporting in 1895 a local recurrence rate of six percent. Several years later, he compiled additional data that, while less impressive than his earlier results, still outshone what other surgeons were accomplishing with less extensive operations: 52 percent of his patients lived three years without a local or regional occurrence.

By 1915, the Halsted radical mastectomy had become the standard operation for breast cancer in all stages, early to late. Physicians in subsequent decades would push Halsted’s procedure even further, going to ever more extreme lengths in pursuit of cancerous cells. At Memorial Sloan-Kettering Hospital in New York, George T. Pack and his student, Jerome Urban, spent the 1950s promoting the superradical mastectomy, a five-hour procedure in which the surgeon removed the breast, underarm lymph nodes, chest muscles, several ribs, and part of the sternum before pulling the remaining breast over the hole in the chest wall and suturing the entire thing closed. Other surgeons performed bilateral oophorectomies on women with breast cancer, removing both ovaries in an attempt to cut off the estrogen that fed some tumors. While neither of these procedures became a widely utilized treatment for the disease, they illustrate the increasingly militarized mindset of cancer doctors who saw their mission in heroic terms and considered a woman’s state of mind following the loss of a breast, and perhaps several other body parts, to be, at best, a negligible consideration.

The Halsted radical mastectomy was on its way out by the late 1970s; within a few years, it would comprise less than five percent of breast cancer surgeries. The demise of Halsted’s eponymous operation had several causes. First, data from cancer survivors showed that the procedure was no more effective at reducing mortality than simple mastectomy, or mastectomy combined with radiation. Second, the radical mastectomy was highly disfiguring, leaving women with a deformed chest where the breast had been, hollow areas beneath the clavicle and underarm, and lymphedema, or swelling of the arm following the removal of lymph nodes. As the women’s health movement expanded in the 1970s, patients grew more vocal about insisting on less disabling treatments, such as lumpectomies and simple mastectomies.

William Stewart Halsted

Halsted’s life and the state of surgery, medicine and public health at the turn of the twentieth century are a rich source of material for a television series, with the built-in drama of epidemic diseases, inadequate treatments, and high mortality rates. But Halsted’s legacy is complicated. He pushed his field forward and introduced innovations, such as surgical gloves, that led to better and safer conditions for patients. But he also became the standard-bearer for an aggressive approach to breast cancer that in many cases resulted in overtreatment. The Halsted radical mastectomy undoubtedly prevented thousands of women from dying of breast cancer, but for others with small tumors or less advanced disease it was surely excessive. And hidden behind the statistics of the number of lives saved were actual women who had to live with the physical and emotional scars of a deforming surgery. The figure of the heroic doctor may still be with us, but the mutilated bodies left behind have been forgotten.

Sources:

Robert A. Aronowitz, Unnatural History: Breast Cancer and American Society. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Barron H. Lerner, The Breast Cancer Wars: Hope, Fear, and the Pursuit of a Cure in Twentieth-Century America. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Howard Markel, An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug Cocaine. Pantheon, 2011.

James S. Olson, Bathsheba’s Breast: Women, Cancer & History. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.